Two essays about textiles and care in my practice.

- Textiles and Care

A couple of years ago, when I uncovered the idea of care as fundamental to my practice, I immediately thought of cloth. It’s hardly news that cloth is all about care; from wrapping newborns to gifting quilts and thousands of years of burying the dead in shrouds. Cloth is undoubtedly care. This is the interpretation of care that I started with, humans expressing and feeling care through textiles, and most specifically for me, through making with textiles.

Cloth and care has always been there, from my 7 year old self who loved costume museums with an obsessive passion. I was of course lucky to have been around in a time when there were not one, but two, in nearby cities that I could visit, for free. Now there are none. Our society just doesn’t care about cloth as much any more. I spent my pocket money in haberdashers. Again, I notice my luck, being born in the 1970s when the Victorian-style haberdasheries still survived. There were two in this middle sized market town, each with banks of glass-fronted wooden cabinets with drawers full of ribbons and threads and handkerchiefs and sewing patterns and rolls of cloth that I couldn’t even imagine knowing how to make into the clothes I loved. I bought a few inches of pretty daisy trim with my pocket money, which I probably sewed onto a dress for a doll, with some very rudimentary stitches. I wasn’t actually brought up around textiles or sewing and didn’t properly learn until I was 12, but cloth was always there: in my grandma’s luxurious clothes, in my aunt’s patchwork-making, and in the occasional visits to my dad’s cousin, whose wife was a stitcher and she repaired the worn paw of my teddy bear with a square of brown velvet. I rarely saw anyone sew in my early years but it was there anyway, in my DNA, passed down through my dad from his mother, a professional seamstress who died before I was born. My dad doesn’t sew but he’s more attuned to fabric than any other man I’ve ever met who doesn’t sew. He was the one who grew up surrounded by cloth and thread and sewing machines and the wheels on his mother’s bike being caught up with threads from the professional workshop she sewed in. I mourn for the sewing childhood I would, should have had with her and proud that I’ve continued the thread of textiles and made it my life’s work. Us textile people are born to it, mostly I think. We love fabric and thread in a way that really makes no logical sense. Most of you listening to this will be textile people and I don’t need to explain it to you. It’s in our souls, this love of cloth, this care for and with textiles and sewing. I don’t know why. But I know it’s powerful. It’s like another language, an understanding for fabric, for the way it feels, the stories it holds. That’s separate from learning the skills of sewing or making with thread. There’s an innate connection with cloth, fibre that I assume others just don’t have. In my mind it’s similar to being musical. My family are mostly musical, my mum in particular. I like music but I don’t feel it in my soul the way she does. I feel cloth in my soul in the same way. She sings, I sew. Two sides of the same complex human experience.

The longer I’ve spend immersed in textiles, the sewing and textile world, the more I am sure that it’s all about care. In 2020 I did a commission for Gawthorpe Textiles Collection called Textiles in Lockdown, researching and sharing stories of textile making in the early days of covid. Textiles, sewing, was holding people together in ways which I can only imagine have held people, mostly women, together in times of crisis for hundreds of years. The extremis of covid lockdowns allowed us to pinpoint the importance of sewing and textile making in emotional repair. I’d already explored that very idea, emotional repair, a couple of years earlier in an exhibition at Gawthorpe itself in 2018. I’d been making work about care for about 10 years by that point, although if I revisit my early career, I was making work about care then too, I just didn’t realise it.

That very early work, and a commission I did in 2008 were related to museum collections. I trained in museum studies and worked throughout my 20s in the museum sector. I had planned, hoped, to work as a costume and textile curator, but the jobs were few and far between and the only one around when I graduated from my MA went to my friend Becky, now a very successful specialist textiles curator at the Burrell Collection. She earned it, she was more focussed than me. I took other routes but the passion for historic textiles never left me, so when I was able to get a job in the education department at the V&A, I was really happy. I didn’t get to work with textiles as much as I would have liked, but I was around extraordinary textiles on display, around fashion theory conferences, around contemporary and historical makers. In many ways it was great, and those years are what made me the artist I am now, even though it meant leaving the job in order to pursue my own textile practice. I was able to nurture my care for textiles, my belief in the importance of cloth, sewing, making and understanding textiles, and learn more about their role in care and connection across the time and place.

It makes sense then that my early work was in honour of those wonderful historic textiles that I cared so much about. As time went on, I started to make work more directly in response to a range of museum collections and historic places, and less about historic textiles directly. In the last 15 years or so, my work has been project-based and mostly made in textiles but not necessarily. When I do work in textiles, the meanings, the stories embedded in old cloth, have become central to my artist practice. The cloth often leads the story as much as what I do to or with that cloth. The oldness of the textiles I use is also important, the thread of museums, preservation and protection runs through everything I do, they are part of the stories I tell. Some years ago I wanted to make some work in memory of my grandad who died in 2012. This is so obviously a story of care – I gathered his gardening tools and the every day cloth of his life. There is care in every stitch, and also in every action – choosing which tools to keep, selecting from the airing cupboard the most interesting and the most useful cloth – and then at the last minute picking up a small stack of neatly folded and ironed handkerchiefs and carefully storing them away until the right combination of idea and material came to me. I stitched the outlines of his tools into those humble handkerchiefs, an act of care for me, for him and for my dad, the connecting thread between us. Around the same time I made a huge piece inspired by amulets and protective garments, covered in details from my grandad’s life and tiny bits and pieces found in his house, stitched onto an old linen sheet, spattered with pink paint that he’d been keeping in the shed for decorating.

Making memorial pieces for my own family is of course some of the most caring work I can do. After years of wanting to do something in memory of my aunt, in 2014 I began an ambitious but tiny project which in the end took almost 5 years to complete. Initially, for my Narrative Threads exhibition I made around 20 pincushions of a planned 46, one to mark each year of her life. I completed the series in 2018 for the Emotional Repair exhibition at Gawthorpe Textiles Collection, where I had initially been to research historic pincushions in the museum. By this point there is no doubt that my work is about care, even though I hadn’t found that word for it. I made memorials, I explored absence, loss and change. I wrote about deeply emotional and personal things and I stitched and stitched and stitched all my care, and all my cares into them.

I am, of course, far from the only artist who uses textiles to express care. There are hundreds of us, all connected through that language of cloth that means we understand the messages we each make. We recognise domestic textiles like tea towels and dusters and we make connections and we explore our own thoughts, emotions and cares when we see others doing it. Textile making is inherently a care-full practice because of all the history and connection that runs through the materials we use, particularly when we use old cloth. There’s such a powerful history of working with cloth and thread. When we choose to work with cloth we are connecting with all that history, all those stories. Embroidery, hand stitch, always feels powerful to me – a direct link to people in the past, around the world, creating such beauty and complexity with just a needle and their own hands.

Sewing for others is, for many people, the epitome of care through making. Hand made gifts are wonderful, although best given only to those who fully appreciate the skill and the care that goes into them. That’s the feeling I’m working with in projects like Criminal Quilts. I made the first series of tiny quilts as metaphorical gifts to the women in the prison photographs. I made more and more, thinking about those women and their hard lives while I was making. Of course I could not actually give them anything, they were long dead, but by creating in their memory, I was making with a retrospective act of care towards them. I used quilts very intentionally as they are so often associated with making and care, the sharing of comfort and security of a warm, safe home. Textiles as my medium, my language, enabled me to express care, and share that expression of care with others. Sharing their images printed on to cloth, and carefully hand embroidered showed viewers that I care and that they should care too. Simply by connecting photographs of women prisoners with textiles adds a layer of care and connection that might be harder to get across in other media. Making their stories in tactile, wearable and domestic fabrics makes them somehow more real, more human and more relatable. In the making, I selected fabrics which deepened their stories, the narratives I wanted to share: I obviously chose black silks when representing widows and white silks when representing married women, but I also chose colourful printed cottons to represent the younger unmarried women, echoing the fashions of the time. That choice is perhaps not so obvious as the wives and widows but for me it felt meaningful and showing care for all of their stories. I worked with old shawls too, which are common in the 1870s and 1880s photographs, using cloth that would be familiar to them, and garments which they would have treasured as protection from the elements. I created connections, threads, between what I could see in photographs to the surviving textiles today and through those threads, made their stories more relatable, their legacies more powerful than they would otherwise have been. Cloth has enormous power in narratives of care, of honouring and paying attention to things that might otherwise have gone unnoticed.

The act of making with textiles is full of care in itself and for me this is only amplified by the careful choices we make in the way we make. My last talk was about productivity, or the lack of it, and the importance of process rather than product, and how this is also a caring way to work. Slow, contemplative, difficult and/or laborious textile processes are the things I choose to do, many of us do. The time it takes is part of the story, sometimes it is the whole story. Textile making is rarely to do with speed and efficiency. It’s never cost effective to hand knit a jumper or to cut and sew a dress. We do it because we enjoy the process. In making textile art, this is even more obvious. The slowness of the process is often the point of the making. Yes, I sometimes make things quite quickly, if the construction is simple and the hand-making is minimal, and in these pieces the cloth and the meaning are the two key elements of the artwork. When I am making in a deliberately slow or careful process, there are three key elements; the cloth and its narratives, the meaning I am trying to convey and the process of making itself. Sometimes the time-consuming part of the process is the idea-development, the testing and the thinking and the making itself is quick. A few years ago I created a piece using an old piece of patchwork where my only intervention was a few cuts in the lining and some almost invisible stitching. The making itself was quick, but the development was slow, thoughtful and considered, and very much had care forefront of my mind. The process of developing the idea, the concept and finding the right carrier for my message was the important part, more than the finished artwork itself – which is just as well as I think it’s often misunderstood or I maybe have not explained it properly. In this same series of works inspired by the stories of damaged quilts, I made a number of pieces that don’t really work as artworks but are incredibly meaningful for me as the maker and were created with utmost care and consideration for both the processes I used and the stories I was exploring. I could not have researched and investigated the stories in the same way if I had not had a textile process as part of the development. One piece involved sourcing a relatively modern patchwork quilt and then carefully taking it apart, noticing and honouring the work that had gone into it, the care embedded in the quilt and its construction. I collected the pieces of fabric and considered the marks of the stitches, the colour variation around the seam allowances where dirt and fading had left the squares with a halo of brighter fabric around them. I tried various things with the pieces and in the end what felt right was to reconstruct the three different prints into three different non-functional patchworks, using clothes-construction shaping methods such as darts in reference to the dress fabrics used. I wanted to make something with body, a sense of the human under the quilt, the (mostly likely) woman who made it. The old quilts I was using as my source had distorted through age or were never flat in the first place and that reminded me of bodies and ageing. The three patchwork pieces don’t work flat on a wall in a gallery. They need to be handled and draped on humans. I tried them later outdoors and they work well as tree stump quilts, following the undulations and angular forms of roots and branches.

The thinking about women’s bodies and ageing led me to another piece in this quilt series. A patchwork made of flesh-toned, draped squares, each weighted with lead causing them to droop and distort the overall shape of the square quilt, honouring, noticing and celebrating the changes in women’s ageing bodies. This has never been one of my more popular pieces, I rarely hear comments on it other than ones of disgust or discomfort although I suspect, I hope, that those who do see it, feel the care and appreciated their experience being made tangible in soft, silky, tactile fabric. Making this work is as much about caring for myself as it is about sharing a narrative, and that’s another thread that runs through my work.

Making with textiles is therapeutic, we all know that. Textiles feel good in our hands, the movements required in hand stitch or weave or knitting are repetitive and soothing. We are truly connected with our material. My friend Deb McGuire talks and writes beautifully and movingly about the embodied experience of hand quilting and how that connects us not only with our own bodies but the the bodies of women who quilted in previous generations. When making with textiles, care is so all encompassing as to be virtually unavoidable. I say virtually as I am talking about artist-made textiles, not mass produced or fast fashion – that is the exact opposite of care, and in many ways proves the point of why it is so bad. Making with textiles ought to be full of care and a system where all the various forms of care are removed from the process is actively undermining humanity. The way I make is intentional careful with resources too. My first products, 18 years ago, were made with vintage and second-hand fabrics. I used some new natural fabrics too, but often felt uncomfortable about buying new, environmentally-damaging fabrics when so much already exists. I wrote a book about it too, Sew Eco, which sits now out of print waiting for me to have the time to revise it for textile artists rather than the makers of functional clothes and cushions it was originally written for. As I tried to move into making to commission for high end interiors, I found my ethics more and more challenged, by the market and by the need for new, repeatable fabric ranges. I soon gave up and moved into making textile art, where production was not the point and I never had to repeat anything ever again, should I not want to. Using sustainable materials has been my thing for so long that I hardly ever talk about it now, it’s just so normal that I forget that other people don’t work in this way, don’t make the same ethical choices as me. And then I despair at the fabric shows and shops at the amount of new fast fashion fabric that is available and being lapped up and regurgitated into quilts and clothes and textile artworks. We don’t need new fabrics, most of the time. Textile art absolutely does not need new fabrics. I understand the pull of the new and pretty and functional and available. I constantly have the challenge of not having quite the fabric to make the thing I have in mind, but it’s a challenge I chose and one that I actually love. I have to be more creative to use what already exists rather than to buy exactly the thing that will work for my idea. The idea and the cloth have to collaborate and maybe the idea has to change to accommodate what I’ve already got. My work has changed radically since I discovered reliable sources of really old fabric, since I built up a stash of 19th century fabrics. I have to be so much more careful with what I do, I have to be mindful of the cloth and what it is suitable for and capable of. I have to supplement with second hand duvet covers and even my own worn out garments if necessary. For all generations prior to ours, textiles were valuable and valued. I chose to continue that way of consuming, of making, respecting the labour, the resources and the skills that went into making this cloth and work with it in a way that allows all that value to be appreciated anew. As I said at the start, cloth and care are utterly intertwined in our history and in our makers minds and that is something we should always celebrate.

I talked briefly in the last session about how much textiles connect us, how there’s such a strong tradition of textile making in community. I haven’t had space to explore that here but I suggest you listen to episode 18 of Making Meaning about Textiles in Lockdown which is conversations with people who make in groups or who organise groups and how not being able to meet impacted their communities of making. The accompanying booklet is more focussed on individual making practice and explores how wellbeing, nature connection and creativity were all impacted by covid, in positive and negative ways. Community and self-care are evident everywhere in this research and it is just as valid and meaningful outside of lockdown as it was inside. Both the podcast and the digital booklet are free.

2. Textile history and care

It’s almost impossible for me to separate me as an artist, a textile artist, from the younger me who trained to work as a costume and textiles curator and textile historian. Textile history is woven through me, museum ethics are fundamental to how I work as an artist and researcher and the study of historic textiles is the core of me as a maker and textile enthusiast. I trained as a historian, curator, a researcher rather than as an artist. I’ve worked out being an artist on the job, so I probably don’t do things in the usual way. That felt challenging for a long time, but in the last few years, I have clarified that I am a researcher first and foremost. One of the ways I explore and share my research is through making, through my artist practice, as well as through writing and teaching.

It’s textile history research that I want to examine today through the lens of care. What stories do old cloth hold and how can we access them? Is collecting, outside of a museum context, a care practice?

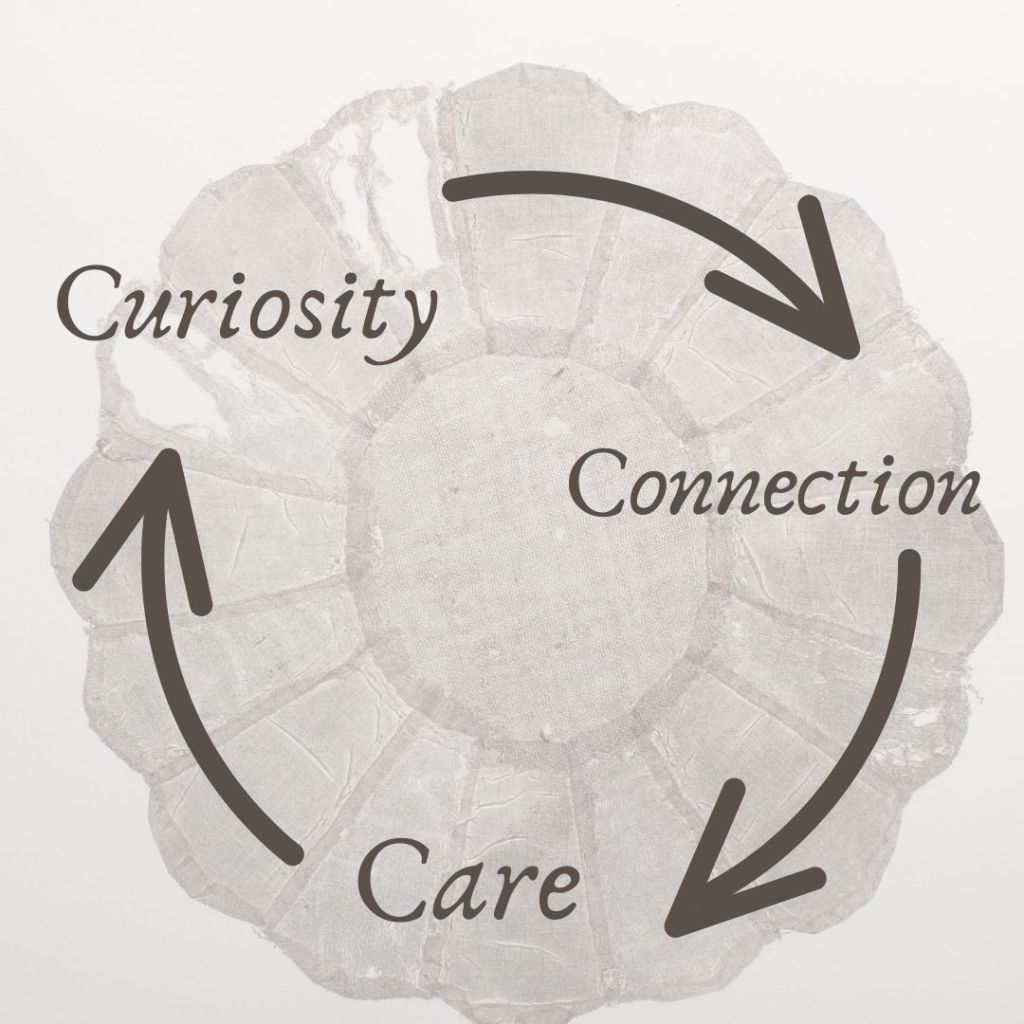

I’ll start by going back to my first Cultures of Care talk a few months ago, about research as a care practice, which you can listen to on Episode 40 of Making Meaning. In that talk I explored how I have become a research-based artist or maybe an art-based researcher and I first shared the model of care practice that I have been using throughout my cultures of care project. I said:

“By exploring and noticing we are caring. By sharing what we are noticing, we are creating, generating and inspiring care by others. Research can open deep wells of information and alongside it, compassion and curiosity. Being curious about the world and its tiny, overlooked fragments of stories is care. Creating artwork which tells those huge or tiny stories is care. This all works as a cycle:

curiosity leads to creativity which leads to connection which leads to care which leads back to more curiosity in a cycle that we care-takers and care-makers share with the world through our creative practice. Through care-taking and then in turn, care-making, a research-based practice cares for both the maker and for the wider world, contributing to a culture of care.”

This model of curiosity, connection and care applies to textile history as much as it does to textile practice, which in me at least, as entirely intertwined. The study of historic textiles is a care practice. We may start with aesthetics, what appeals to us visually, but with further curiosity, we can deepen our connections, our engagement with the stories held within the cloth. Knowing those stories, or guessing those stories (which is more accurate) is why we care. The aesthetics alone, the beauty of the textile, may be enough to make us care, to make us want to contemplate and handle this cloth. My approach through all my varied ways of working, is to go a step further, many steps further. I am less interested in cloth that is simply beautiful than one that has more evidence of human stories and textile history embedded within it.

I care enormously about old cloth, it isn’t just a material for making, it’s important, powerful and meaningful in its own right. I sometimes don’t want to cut or stitch it at all. I am very careful – and I use that word intentionally – full of care, about what I cut and what I don’t. Even cloth that I use, that I cut and stitch, I research, I study it first. The stories it holds are fundamental the the work I am making, so I need to understand what the cloth means to me before I can use it in my work. That’s where the connection comes in for me when I am making. The textile and the narrative have to connect. I talked a lot about this in the last talk about textiles and care so I won’t repeat myself here. Instead, let’s have a look at the stories of care that textiles can hold and how that creates connection.

Cloth holds the story of its production, the growing fibre, the processing of thread, the construction through weaving to produce the textile base. Then there’s finishing and dye, there’s movement and retail, there’s purchase and storage, there’s use or preservation, there’s the buying and selling of old textiles, or the clearance of old stashes. That’s even before the cloth has been used to make something else.

All of these stages involve humans, many of them, most of them, involve women. Many of those stages can involve exploitation and forced labour, environmental degradation, abuse of animals and resource extraction. As we all know, textile manufacture is still lacking in care for the humans, creatures and planet that produce it. Textile manufacture from the industrial revolution onwards is generally not a cosy subject. But we need to know this stuff, we need to notice, we need to care.

My own personal passion is constructed textiles, cloth that has been cut and sewn into other things – garments, patchwork, church vestments, bed linen, pincushions and purses, or cloth that has been stitched-upon. I love textile objects and I love the stories of making that they hold – the process of sewing is the magic for me, usually. This is generally the less challenging end of textile history, as it is somewhat less likely to involve the horrors of cloth manufacture, though not necessarily. The thing that fascinates me most in this stage of textile history is that almost all of the work was done by women. Again that’s not exclusive and we obviously cannot tell most of the time who the makers were, let alone anything about them. But in some cases we can and that is really exciting.

The third stage of textile history and care is about the value and the survival of the objects that we see and hold today. The financial value of textiles has dropped over the last couple of hundred years, and plummeted in the 21st century. It’s all too easy to forget just how valuable many textiles were for hundreds of years, from the luxury end of imported silks to the everyday handwoven linen or wool – its all valuable according to your income level. Cloth was never taken for granted, never wasted, in societies where the intensive human labour and skill to produce it were well understood, respected and valued. That value also connects with the makers, the stitchers, the women who usually made the objects from cloth and their social value, their place in society and economies – generally right at the bottom. Making with cloth, constructing objects, adds value in an economic sense but it also adds other kinds of value. Making, sewing adds all kinds of social and historical value to objects, making an 18th century dress hold far more stories of care, more than a length of luxurious but untouched cloth. The cloth of course has many stories, but the combination of cloth and construction adds more layers and meanings, just as the wearing of a garment adds more too. A pristine, unworn garment or unused object is traditionally considered more valuable in a museum context, as the makers intentions, the perfection of production and construction are most apparent. Wearing, using things degrades them, or to my mind, positively changes them. That change or degradation is another layer in the story of the object, but depending on what you value most, that story may not be considered important. Amongst textile objects, sewn things, clothes have the most stories because of that history of wear, the body in the garments and the often complex wearing histories that can sometimes be found in a single piece. With older cloth, more valuable cloth than we are used to today, there will be stories of making, wearing, storage, remaking and even total deconstruction within one piece. The post-construction phase is always fascinating to me. The use, misuse, preservation (accidental or intentional) and the care that happens in each of those stages are often apparent in the object, or we can theorise about them at least. There are often multiple stories, multiple owners or indeed carers for this piece. Laundry, mending, remaking – in high-end garments these tasks were unlikely to be carried out by the same person who wore them, and again, those care-takers are usually women. The longer-term caretakers of women’s stories in cloth are usually women too. Family textile collections tend to be gathered and archived by women, and they tend to be women’s garments or women’s work that is kept, whether or not the pieces were made by the women in the family or just worn and valued by them. In other cases there is no apparent care beyond the lifetime of the original owners. Once-valued and valuable textile objects are disposed of all the time, they become rags, they go to landfill, they rot and fade and vanish. These stories all matter, these are all stories of care, given or missing. The implied histories, the unknown stories of why this particular pincushion or petticoat has survived, how it got to me in the 21st century, is an open book. These are the histories that the object usually can’t tell, and this is where artistic licence, informed by textile history, comes in for my textile-practice.

Much as I love pristine, unfaded, old embroidery or perfectly-preserved Victorian dresses, I am fascinated by damaged textiles. This is all about care, or the lack of it. In my own textile making practice and artist practice, I am interested in the missing, the lost, the stories that we don’t have, things we didn’t even know about. I love negative space, cutting away cloth and leaving gaps and holes to tell the stories of loss and damage. My fascination with damaged textiles is part of the same curiosity about care, lack of it, and missing stories. Over my many years of working with textiles, studying historic textiles, in museums and in my own practice, I have learned to read cloth and the stories it holds. I’ve learned to read damage too, I can usually tell the cause of damage, the actions or inactions on cloth that have led to degradation or destruction. Some of this I learned as I trained to be a textile curator, some of it I have learned as an artist-researcher-collector of old cloth, through my own observations and experiences. There are so many factors causing damage to cloth, some of it is reversible, repairable – through skilled stitching, some of it would only be treatable by specialist conservators and some of it is just not repairable at all. I’m in awe of textile conservation, fascinated by it – in fact in my early teens, that was my career of choice, rather than curator, but I soon discovered you needed to do chemistry A-level and that it was as much science as stitching, and that didn’t (and still doesn’t) appeal. The stitching side of conservation is still a huge inspiration to me – I’ve created work very much influenced by that practice and continue to learn from conservation practice whenever I can. Repair and remaking is a huge part of textile and craft practice today too – many makers work with repairs as their practice and it is an important field of academic study too. Although I’ve always been a keen mender, a repairer of old clothes and textiles, I have chosen not to focus on repair in my own research or making work. There are many others doing this with more skill and dedication than I could offer and I have chosen to focus on the un-repaired, the damaged beyond repair and re-use so the study of the damage is more the centre of things than the act of repair. Damage inspires my work, influences my creative decisions, informs my collecting, but it is not in order to repair things. I was recently asked to share some repaired work in an exhibition, but I had to reply to say that I don’t do typical repairs as my practice. Instead I am showing one of my Garment Ghosts, ethereal sewn pieces made with the remains of damaged-beyond-repair clothing. These are pieces where I have used the textile fragments, I have repaired in a sense – preserved and highlighted the damage as much as the remaining cloth. They are constructed with conservation-inspired processes and materials. The development of this body of work continues, 10 years on from the first pieces – damage continues to run through my creative ideas. What first drew me to work in this way was the ready availability of badly damaged clothing and my desire to honour the labour that went into the pieces, to notice the value of the cloth and the construction, the women who made these pieces and those who have had guardianship of them since they were first made 150 years or more ago. My process is one of care of cloth and care of the unknown narratives of makers embedded within that cloth – the spaces in its history.

Since starting this body of work nearly 10 years ago, I have amassed a large collection of damaged clothing, quilts, embroidery and fragments of cloth. Some of this will be used, is being used, in my making, but the majority of it is for research purposes for the twin reasons of it being too damaged to use and too interesting as a complete fragment to be taken apart. I find the stories embedded in made objects and their narratives of use and preservation to be more interesting than the fragments of cloth made into something else, usually.

Sometimes I worry that I am too much the curator, collector of cloth (of holes in cloth) and not enough the artist because I don’t use most of the cloth I own. Of course, I said right at the start of this talk that I am researcher first and artist is one of the ways I share my research, so I am tying myself in knots unnecessarily. Through creating collections of intact and damaged textiles, I am collecting stories of making. I am the keeper of those stories but most importantly, I am illuminating and discovering those stories, they are no longer lost or forgotten. My collections, the stories in that cloth are the embodiment of the labour, women’s labour that went into the making, constructing, wearing or caring.

With my own collections I am able to study in a way not possible in museum collections. Hands-on study of old textiles is a care practice for me. I care for the cloth and the process, the absorption, the learning, and the excitement is self-care. Being able to do something that I love is the best care. In the same way as making, studying cloth that I own is mindful, meditative, inspiring and joyful. Part of the joy of damaged textiles as a field of study is that I can’t really make it any worse, I don’t have to worry about further tears, light damage or moth holes. I can, if I wish, unpick, as I did with garment ghosts and do sometimes with other pieces. I often don’t though. I don’t need the fabric to work with, I have enough other cloth, unmade pieces, to use in my work. This close study is both functional, understanding construction methods and creative – inspiring stories, ideas and ways to express through making. Through this close engagement, I can feel directly connected to the past makers, wearers, users, preservers or damagers of this cloth. The fabric is a window into unknown lives, motivations, labour, care and no doubt also lack of care. Some women made things because they had to and they hated every minute of it. Some pieces are badly made, without skill or care and these are valuable stories too, but ones which are less likely to appear in museum collections. In 2016 I studied the Quilt Association’s archive to inform a new body of work I exhibited with them in the same year. I asked to see the most damaged, the least-accomplished making and the pieces which had a provenance, a known maker. There was consternation – offering of finer pieces, more interesting fabrics, better stitches…I loved the remains of quilts, the functional over decorative and the histories of the quilts used as decorators dust sheets or horse blankets. From those pieces of inspiration, I created quilts made of fragments, holes, and half-histories. I looked at how quilts were life or death for poor women, made to sell or made to keep warm. The stories of these quilts are deep, they are stories of care, past, present and future and they continue to inspire me, years on.

Museum objects which I can’t touch, turn over, poke at, let alone unpick, are still enormously important to my creative practice. One of the pleasures of being an artist-researcher rather than a curatorial-researcher is the breadth of how I can interpret pieces. Although my creative work is rooted deeply in textile history knowledge and museum ethics, I can as an artist, tell stories beyond what the cloth actually reveals. In the summer I visited my favourite historic house, Chastleton in the Cotswolds, probably for the 10th time. This time it was for a specialist textile tour allowing a small group into the house when it was closed to visitors to look more closely at the many amazing textile pieces that have been in the house for hundreds of years. Sadly I picked a day when the specialist tour leader was not able to come and the tour was considerably less specialist than I would have liked. However, it did give me time to see some favourite pieces and talk to others on the tour about their thoughts on what we saw. For many years I have been researching trapunto or corded / stuffed quilting, and yet I had forgotten that there was a huge trapunto quilt in Chastleton. I had seen it before but perhaps that was before I planned to write a book about the technique and it hadn’t lodged firmly in my leaky memory. This was not like a museum store visit where pieces are laid out in study rooms for close examination under decent light, taking as long as you need, this piece was on the bed where it lives all year round and the group wanted to move on after 10 minutes or so. In the evening after the visit I sat to write about the quilt, a rare example with a known, named maker. I wrote about the things we don’t know, can’t know – her motivation, her feelings for making, what it was like working on this enormous quilt for many years, keeping it clean and white and actually finishing it. In this written piece I ask more questions, did she work alone or was there someone helping her, did she stitch for hours at a time or fragments here and there? How has this quilt survived so well for 300 years? Who has slept under it? Who has cared for it, before the National Trust?

Writing these textile narratives is a care practice. Noticing and being curious about something other than the stitch quality is a care practice. Noticing the woman behind this piece is a care practice.

Knowing the maker is a transformative thing for textile history. Most of what survives is detached from its creator. This quilt by Anne Whitmore has far more known narrative than an equally delightful similar quilt in a museum collection, divorced from both its maker and its home. This quilt still quietly residing on the bed it was made for, in the house it has always been in, is powerful in a way a quilt resting in a storage box in a museum isn’t. Both are important, but it’s worth noticing the difference. Noticing is care.

At the moment I am working closely, deeply and with considerable care on the work of a known maker – Mary Linwood. She was an 18th-19th century embroidery artist of huge skill and fame in her lifetime and a good few pieces of her work survive in the collection of her home town of Leicester, where I am curating an exhibition of her work alongside my own. Mary Linwood made her embroideries with a very different intent to most of her contemporaries. Middle and upper class women stitched mainly for the home, for domestic purposes – which does not in any way make their work unimportant – it just means that their names are usually no longer connected to their work. In Mary Linwood’s case, she made for exhibitions and for sharing, more like professional artists today, like me, than her contemporaries. Her fame withered rapidly after she died and her legacy is not what it should be. My work, my research into her making practice and her life, is built around care, much like my other projects. I care deeply that she should be respected and remembered. I am studying her surviving artworks with a curiosity and connection that only close study can allow. I have been able to examine her embroideries close up and sometimes from the back too, and through this have developed a material understanding of her making process. Had I remained in the curatorial world, made it as a textile curator, I might still have come to Mary Linwood in my mid-life and might still be doing an exhibition about her, but I would be doing a different exhibition, I would be seeing her, understanding her in a vastly different way. Only through making, through material understanding, can you learn to read other making with depth and care. Curators, researchers, academics in textile history have enormous knowledge and skills I don’t have, but as a maker I have a different route into understanding, into reading the stitches of others. The knowledge of making is important, understanding processes and materials is important, the valuing of the minutiae of historic textile making is important and it is all about care.

I could, and I often do, write at length about historic textiles and care. The artworks I make, often from historic textiles, are infused with this stuff, these histories, I am infused with these histories. To circle back to where I started, the circular process of care: curiosity and research creates connection and engagement which inspires and deepens care and generates more curiosity. This is manifest in my own creative practice of research and making, utterly intertwined. The sharing part of my practice is so important to me too. Writing this has been valuable in so many ways, and I hope has value for you too. This year, through the Cultures of Care project, I have realised just how important textile history and making is to my own wellbeing, my own self-care and because of this I will be focussing on this more closely in the next few years. It’s always been there, of course, but in the last 5 years or so I have done more and more behind the scenes work with arts organisations, consultancy, mentoring and artist development work. I love this work and find it rewarding in many ways, but I love textiles more and I hope to get back to more research, writing and making about and with textiles – and of course sharing this research with you in many different ways. Thanks for such an important part of this process and practice.