A delve into verdure, or the lack of it, in textiles and in my studio

As I sort through my textile collections, re-packing them into new (antique) drawers, I notice how little green I actually have. I don’t often work with green cloth, I don’t tend to wear a lot of green either, yet natural places, the green of plants is so fundamental to keeping my soul growing that I seems surprising that there isn’t more green in this sacred space of my studio. I have plants, often the slightly less-vigorous ones that don’t earn space in my living room, ones that will withstand the full sun of the studio windowsill and survive the neglect that seems inevitable – my focus is elsewhere when I am in here.

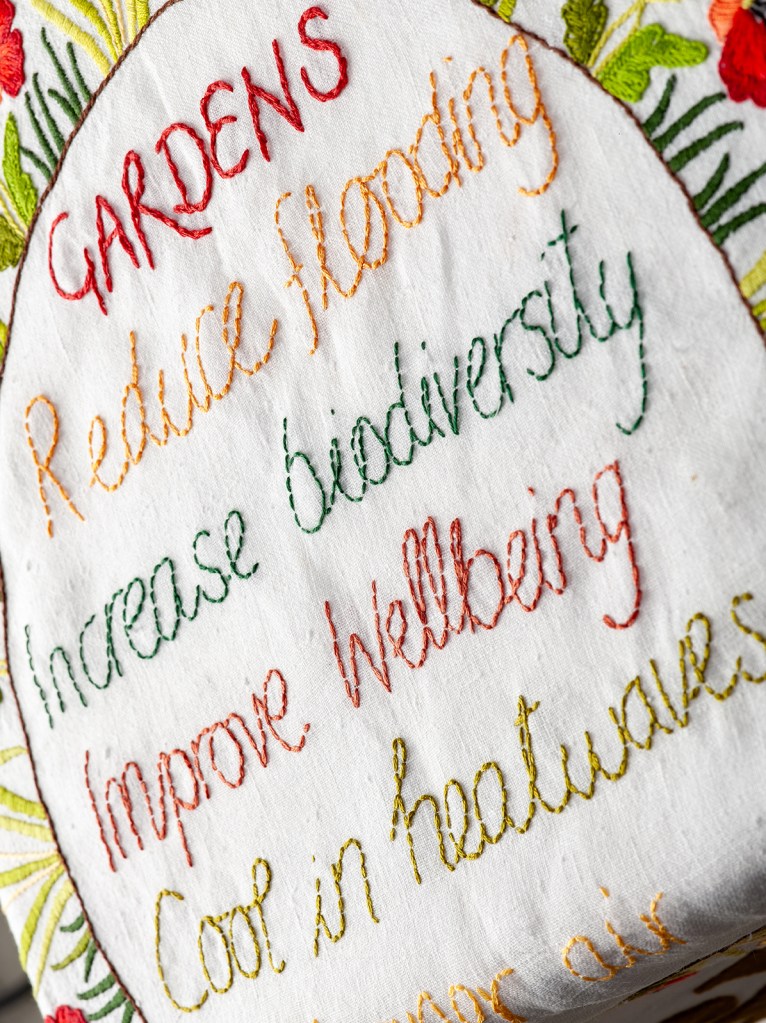

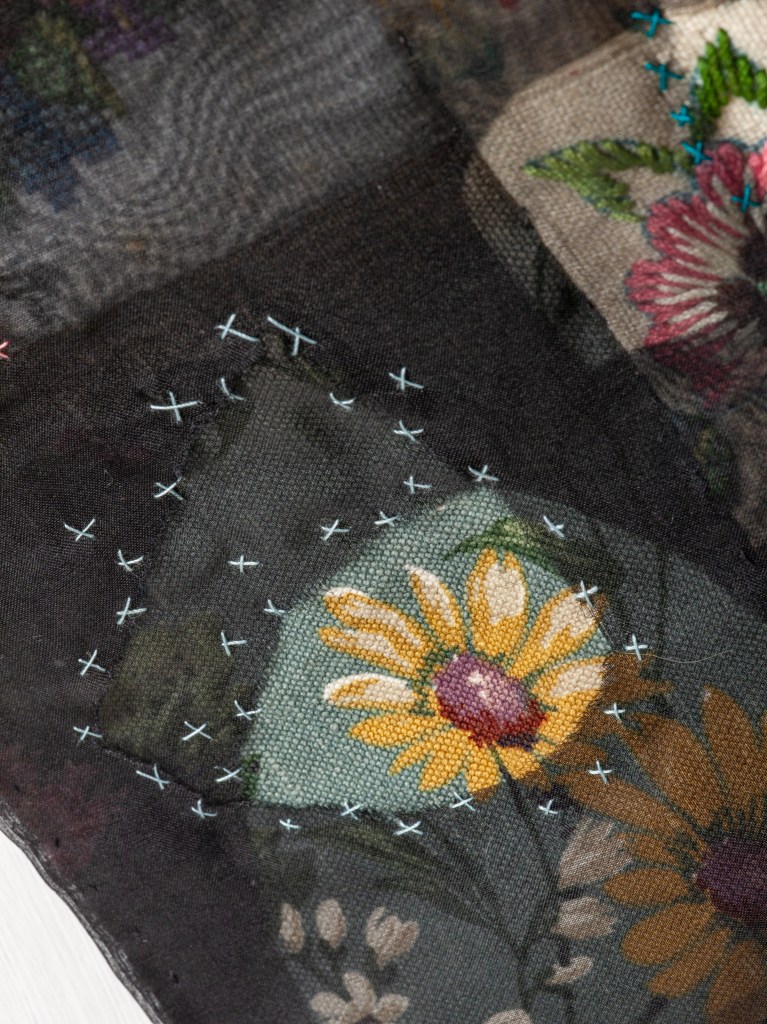

I made a number artworks a couple of years ago in a series called Front Gardens. They were not particularly green, although the protest banner Make Gardens Green Again (above) does have yellow-green felt lettering. This, like most of the works, explores the loss of green, the destruction of gardens and the covering with concrete, so grey and black predominate, along with a touch of red for danger.

I work with what I have of course, so not having a stash of green fabrics means my work doesn’t have much green in it. A lot of what I have is natural or unbleached – cotton sheets, simple vintage linens, cotton or silk lining fabrics, reclaimed garment scraps, old wedding veils and a vast supply of Victorian garments. They are not green either – black or cream silk and white cotton predominate. A dozen or so years ago, when I resolved to work mainly in antique fabrics, I had to settle for what there was, and what there was was mostly neutral, so that is what I have. I have come to love neutrals and the many and varied shades of off-white and light browns. My adding of colour comes with stitch, mainly, but my thread drawers show little in the way of greens too. Green is surprisingly difficult to produce with natural dyes, requiring an over-dyeing of yellow with the more complex process of indigo, which I have never tackled by myself.

I do have some green items, even if not much cloth or thread, including a ragged and moth-eaten green silk dress from the 1920s, and a bag of fragments of a blue-green beaded silk flapper dress of the same decade but little else. Perhaps this is a blessing, saving me from the risk of arsenic-laden fabrics, coloured in the same poisonous way as the infamous wallpaper. Scheele’s green was developed in a lab from arsenic in 1775 and by the mid 19th century it was highly fashionable despite the technical flaw of it being rather poisonous. What I’ve read points to cases of death and illnesses amongst the hard-pressed dressmakers working with this stuff as well as the wealthy wearers, but surely the dyers, the drapers and lady’s maids cleaning and preparing these clothes also suffered.

The dressmakers would have had the majority of the handling of it, with dresses like this (recently seen at Calke Abbey), taking hours to hand sew. The wearer was more protected by limited handling of the cloth, and wearing it only with layers of undergarments protecting her skin from the toxic green silk. [I don’t imagine this one is actually dyed with arsenic, otherwise the National Trust would not have put it on display.]

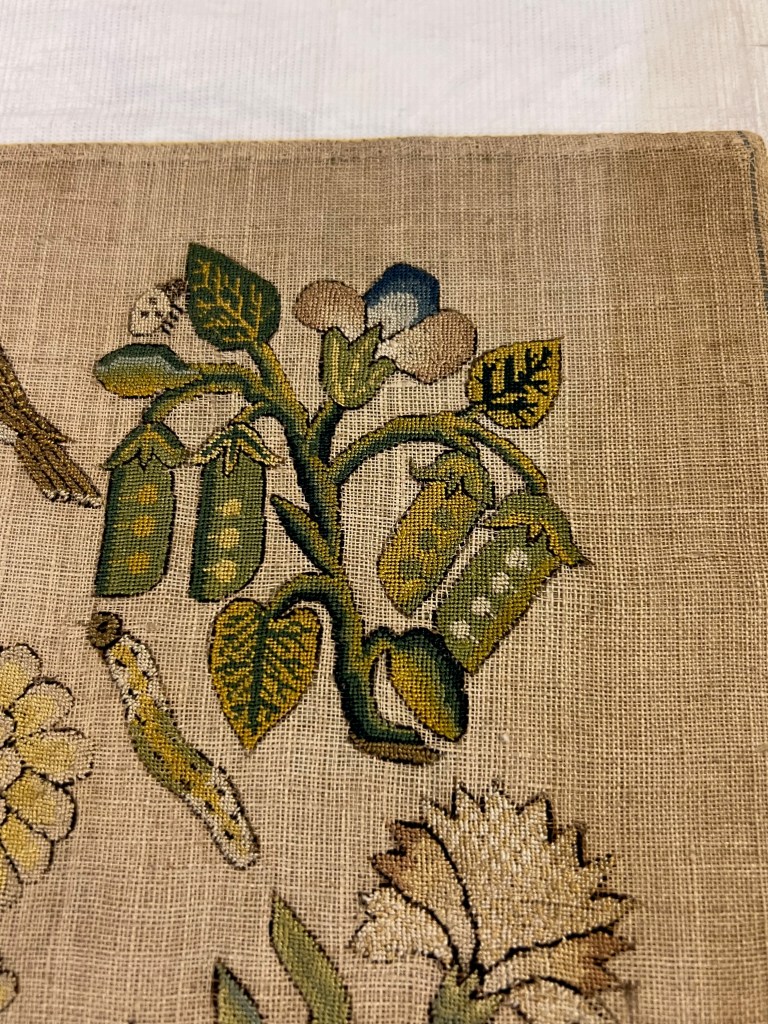

When you think about the process of producing green previously, you can see why a new-fangled dye would be exciting. The combination of yellows (from locally-growing plants) and blue from indigo (or earlier, woad in Europe) could produce a huge range of shades and variations, but they were all familiar, having existed for generations already and the passion for newness in fashion is nothing new today. The introduction of indigo dye from the 16th century superseded the native woad in Europe, and would have created a different range of colours as the two plants are not exactly the same kind of blue. Both indigo and woad are pretty colour-fast but yellows, particularly weld as favoured in England, are more susceptible to fading. This is what gives our country house tapestries more than a hint of blue landscapes and trees. What was intended as verdure, a green oasis of flowering plants, abundantly leafy trees or grassy hills are now inky or watery blues. The yellows depart, slowly, over hundreds of years and leave us now after 400 or more years, with an indigo forest-scape. It’s not clear how long it takes for weld to succumb to the ravages of UV light, but tapestries were valued, moved, traded, inherited and continued in desirable for a long, long time, it may not have happened all that quickly. Once the colour is gone, you can’t get it back. Colour-loss through light exposure is permanent. Even 21st century science cannot change the course of time and you can’t re-dye woven-in strands of wool in situ (though that hasn’t stopped some trying with paint in generations before conservation science).

Although dyeing green required a two-stage process, and one of those was the more technically-challenging woad or indigo, green remained a relatively cheap colour of fabric in the middle ages as local dyers had got the skills and the materials to hand. The fashion for verdant tapestries would not have been possible had the green yarn not been readily available, along with the constituent yellow and blue, plus the vibrant madder red in its multiple shades. These plus a touch of black and white and pale tones of the other colours were all that you needed to produce a spectacular woven picture in tapestry.

300 years or so later, Mary Linwood worked her tapestry-like embroideries with a similar range of natural colours. She had access to New World colours which her medieval forebears could only imagine, including purple logwood and bright cerise pink cochineal, although neither appears prominently in her surviving works. For all that she stitched landscapes, leaves and grassy foregrounds, she used very little green. Over the last 18 months, I have seen every extant piece in UK museum collections and a couple in private hands too, and I have seen hardly any green. I had assumed that the greens had faded, like the tapestries, but there’s also very little blueness so that can’t be the case. Looking at the backs of some of her pieces, it’s clear that she really didn’t use green – maybe in fear of fashionable arsenic in the dye or maybe in reference to the painters she followed. Gainsborough was fond of autumnal colours rather than vibrant greens, so perhaps Linwood was influenced by the availability of pigments that the painters used or their own preferences. She is thought to have acquired her worsted (wool) thread through the abundance of hosiery manufacturers in her home town of Leicester, and although she was said to dye some herself, she undoubtedly made use of the skilled colourists working on the yarn for stocking knitting as well. There is so little surviving material related to late 18th century stocking production that I cannot find out of green was in or out of fashion and if the colours that were in abundance had an impact on what Mary Linwood chose for her embroidery. The worsted thread she used was not being spun for the express purpose of embroidery, as far as I can tell – the majority of domestic and professional embroidery used silk, and had done for generations by this time.

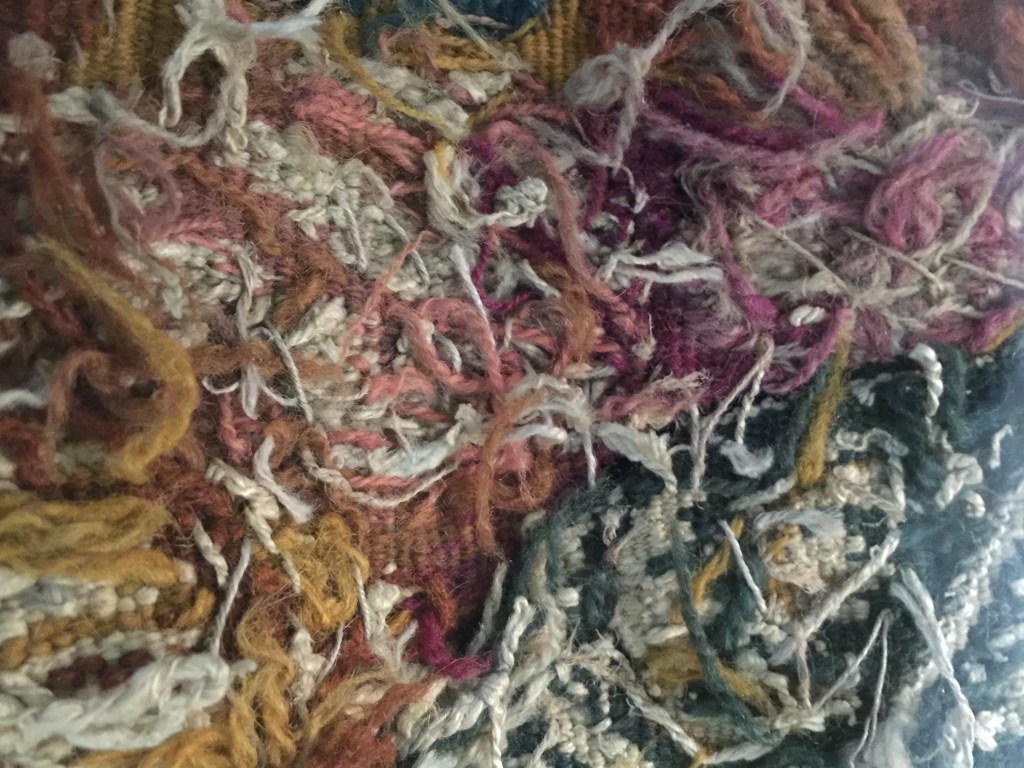

Over the summer I visited Birmingham Museums store for a study session on 16th and 17th century embroidery. They are abundant in flowers and foliage and plenty of greenery. One of the stump work pieces was damaged, with the surface of raised pieces worn away revealing the stuffing used to create the texture. A charmingly-striped parrot revealed innards of bright green wool fibres. Another had a glorious grassy mound in five shades of green from chartreuse to teal. A petit point was replete with unfaded greens including peapods, caterpillars and brightly-veined leaves.

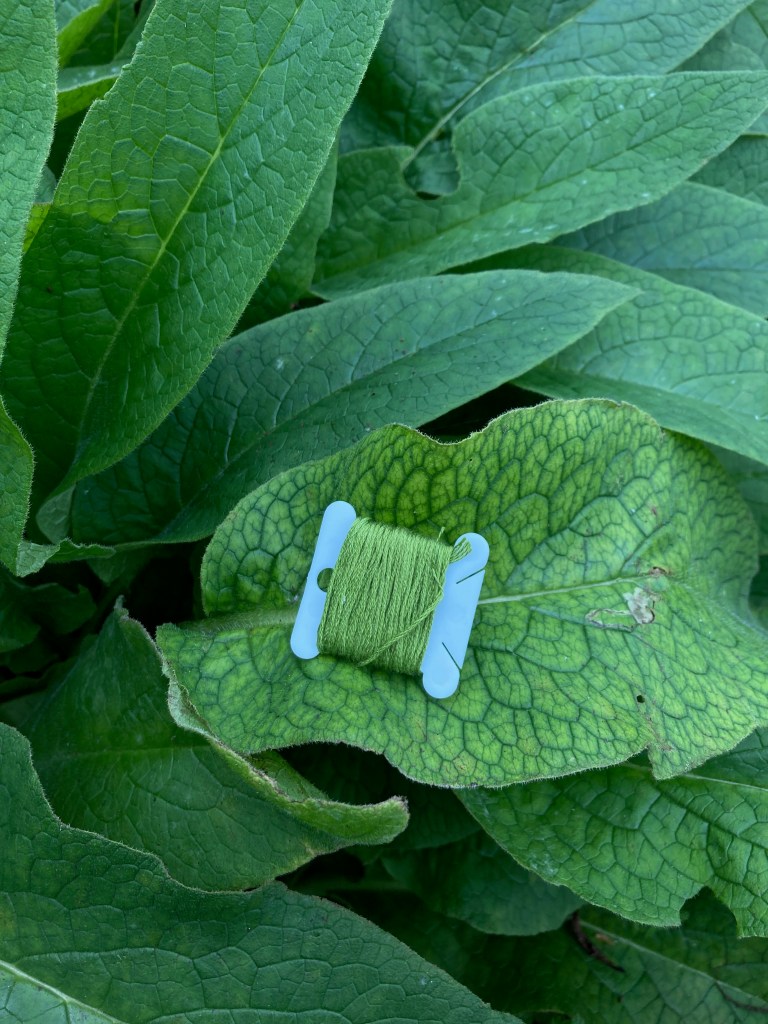

The varied greens of plants was something I explored during my two nature-based residencies in 2023 & 2024. When I learned that we can distinguish far more variations of green than of any other colour, I wanted to explore this through workshops in community gardens. We talked about why humans needed to distinguish plants in such detail and we used my enormous variety of threads to colour match the various greens of grass, evergreens, herbaceous plants, succulents and trees. This inspired me to create a stitched diary of colours throughout the autumn in the second community garden, ranging from orange calendula to brown soil.

Paying attention to colours, to the details, to things we don’t ordinarily notice, is a key part of my practice, running across my work in gardens and with community groups to my study of historic textiles in my own collections and in museums. Focussing on a single colour is a similarly narrow exercise, prompting the consideration of seemingly unconnected stories and weaving them together. This is my life’s work.

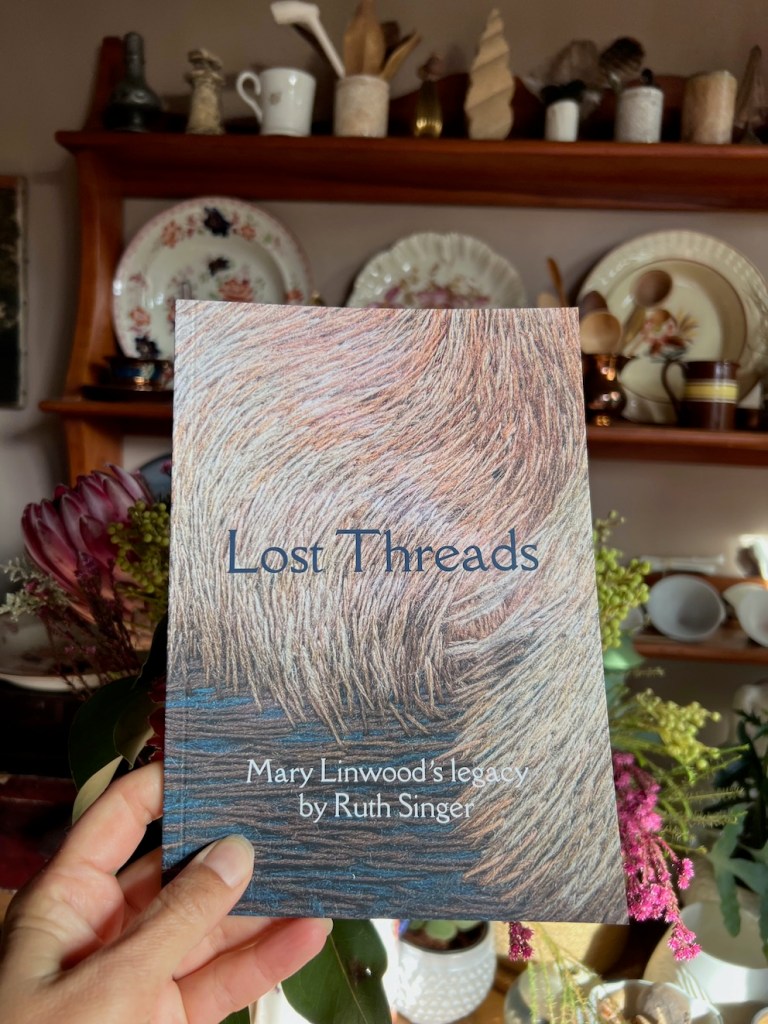

Lost Threads: Mary Linwood’s Legacy by Ruth Singer

60 page A5 booklet covering the Mary Linwood: Art, Stitch & Life exhibition. This catalogue includes image of all the Mary Linwood embroideries featured in the exhibition including several close up details and the reverse of several too. There is also a section on Ruth’s own work for the exhibition.

Let me know what you think