The under-appreciated originality of Mary Linwood (1755-1845)

This essay is inspired by the prompt of Originality, posed by Beth Kempton on Substack for the Summer of Substack Essay Festival. You are welcome to subscribe to my substack but for now I intend to keep copying my writing over here on my website, so you could just subscribe to this instead and get all of my posts by email (it should pop up in a little box on the bottom right of the page).

The prompt of Originality is, to an artist, a bit of a touchy subject. It’s supposed to be what we are all striving for, although some seem happy enough to not bother even attempting this and appear to strive for being derivative and indeed successfully pull this off. The pursuit of originality must surely be one of the main causes of angst and arguments amongst artists. We worry that our work is not original enough, then, once we have found our unique voice, we worry, and despair, when others copy what we believe is our own. Originality, like most creative endeavours, is not possible to quantify or to prove. What even is originality, in creative practice? I’m not sure I know, even after 20 years in pursuit of this most slippery of ideas. Personally, I am now more focussed on the pursuit of integrity, feeling that my work is true to my personal values, that it has a clear and impactful meaning and aligns with my desire to make a positive impact on the world. I have no interest in making something that looks like another artist made it, but inevitably that will sometimes happen and likewise, others will make things heavily inspired by my making, the work I have shared and the techniques I have taught and published. I am quite philosophical about this now, knowing that by sharing what I do, others will absorb and reinvent it, in the same way I have absorbed and reinvented historic textile techniques and ideas, and no doubt, the influence of other artists’ works I have seen in my lifetime.

Textile making, embroidery in particular, has grown from a tradition of copying, repeating and reinventing established or traditional motifs, designs, stitch patterns and uses. For generations, originality of design was not part of the work basket of a domestic embroiderers. The stitching was the point, not the drawing it was based on.

“Though completely lacking creative talent and invention, Mary Linwood was an admirable craftswoman.”

Bea Howe in Country Life, 1945

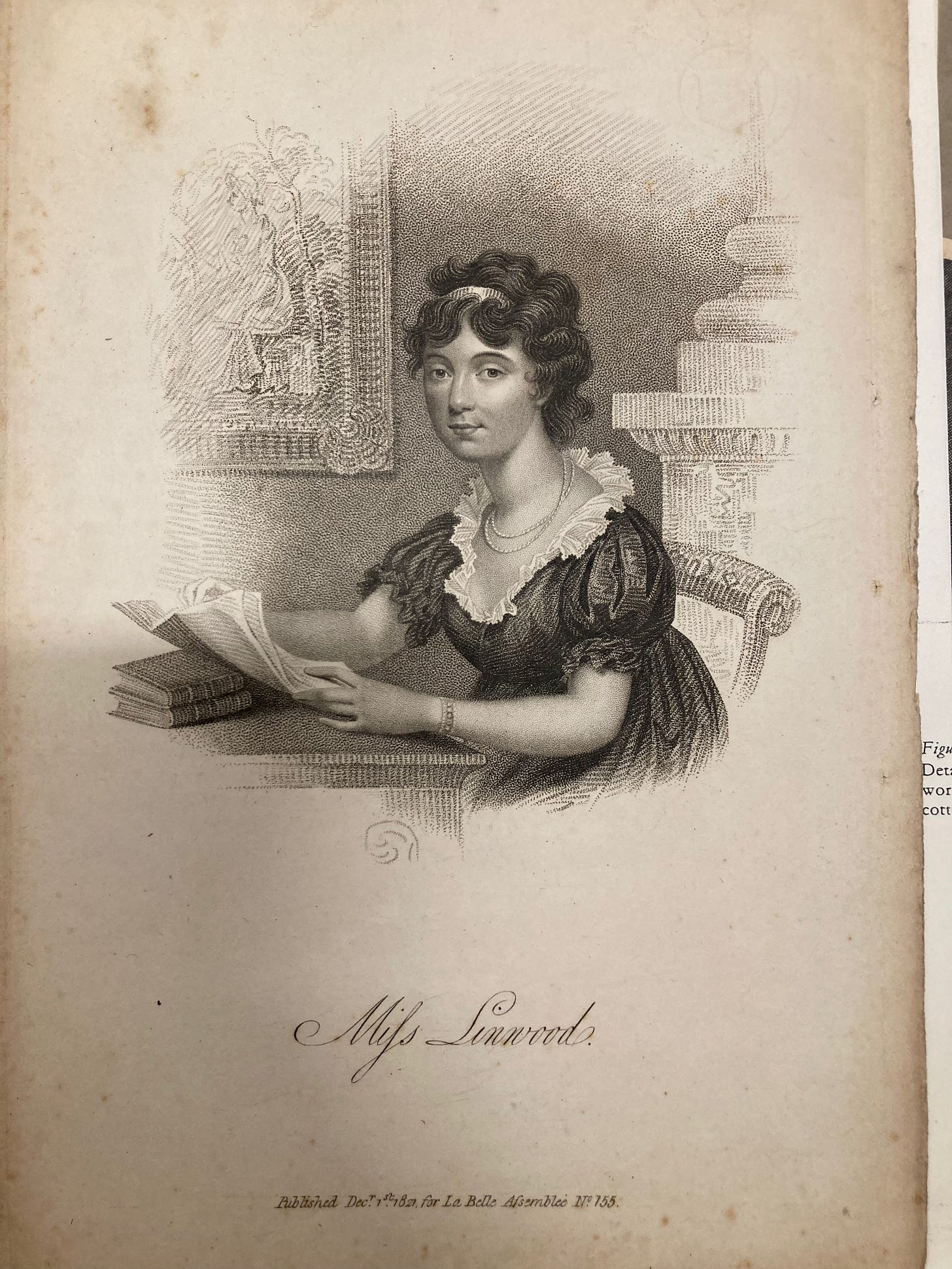

Engraving 1821 showing Mary Linwood. Leicestershire Record Office

As I prepare for the opening of my exhibition Mary Linwood; Art, Stitch and Life, I am braced for the onslaught of the highly unoriginal viewpoint that she was just copying paintings and was not a ‘proper’ artist. Since her death in 1845 at the grand old age of nearly ninety, her extraordinarily skilled renditions of famous paintings in wool embroidery have been derided and belittled by art historians. During her lifetime, she was celebrated and successful, exhibiting her often monumental artworks in her own gallery – the first owned by a woman in London, and surely the first anywhere to focus entirely on the work of just one female artist working in needlework. The idea of creating a public gallery of your own work, as a single woman in early 19th century England, is the epitome of originality and creativity, never mind the ground-breaking work she did with woollen threads.

Those works in wool (or worsted, to be technically accurate), were admired (and sometimes publicly-desired) by royalty, aristocracy and the upper- and middle-classes alike at the height of her fame. She made versions of paintings by Gainsborough, Reynolds and Joseph Wright (of nearby Derby) in her school / home in the industrial city of Leicester. As her fame grew, she was invited to stately homes and country mansions to make copies of their paintings, which she then exhibited in her London gallery, enabling thousands to see versions of paintings that could not be reproduced in colour in other ways and could not be gathered together in a public space, accessible for 1 or 2 shillings. In intent and execution of her public-education ambition she was pure originality, finding ways to extend her collection of works through networking with artists and commissioners of paintings. She had, in some ways, had her hand forced in this endeavour by the Royal Academy, the gathering place of painters, banning both needlework and copies very soon after its establishment. The separation of needlework from painting by the RA created a still persistent divide between ‘art’ and ‘craft’ which had not properly existed before. Mary Linwood, as a young woman, learned her art of needlework following printed patterns, established stitching traditions and the copying of existing examples.

There was a fashion in the 1780s of making silk versions of popular engravings in black silk thread (or sometimes hair) on white silk ground. A beautifully-stitched version of Charlotte at Werther’s Tomb, believed to have been stitched by Linwood is in the collection of Leicester Museums. The sight of paintings, perhaps owned by the family friend and mentor Matthew Boulton, may have been what inspired her, alongside her mother, to begin stitching coloured versions of artworks, this time in the more affordable wool, spun and dyed in Leicester for the hosiery industry. By using prints, drawings, pattern books and eventually paintings as the model for embroidery they were following in a long-established tradition. Embroiderers used pattern books, previously stitched samplers and professional drawings to create their embroideries. Some no doubt adapted and reimagined elements of established patterns and probably also wildly invented their own imagery, but the work was not assessed or valued on the basis of the originality of the design but of the quality of the stitching. Professional tapestry weavers wove to the cartoons produced by draughtsmen, Mary Queen of Scots produced her quirky embroideries in captivity from printed sources. It was totally normal practice, so to my mind, judging Mary Linwood harshly for using other people’s imagery to inform her stitching, is entirely pointless.

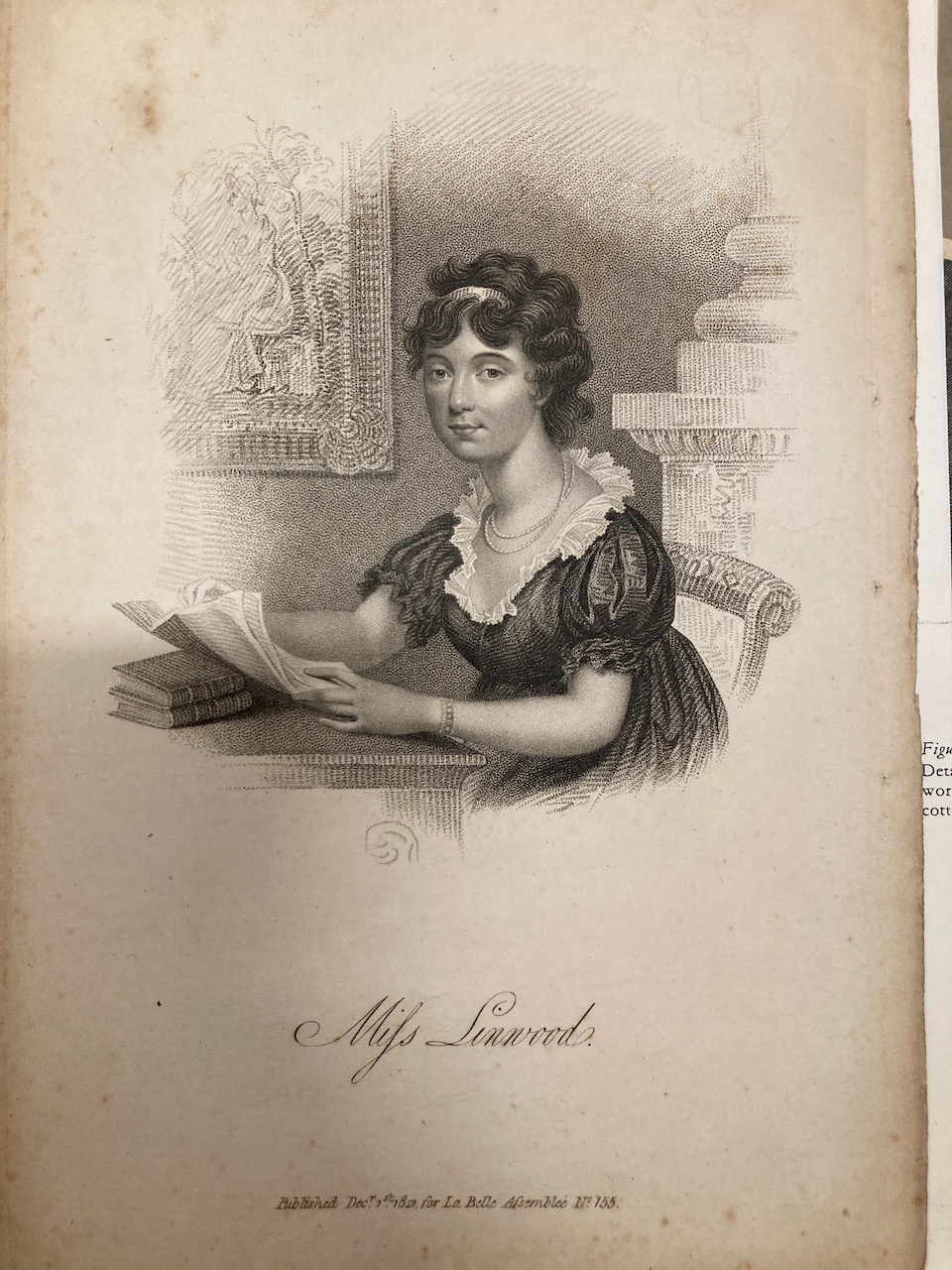

A detail Mary Linwood’s stitched version of a painting by Moses Houghton. Leicester Museums

Originality of design for needlework is a different skill to the needlework itself, and not one that women of her generation and class were expected to pursue. She did in fact make embroideries of her own drawings and paintings, and the way she was able to copy paintings in exquisite detail, shows that she was actually highly skilled in drawing – learned in part, no doubt, by copying other drawings, engravings and printed images, as all learners, male and female, did in that period. In the decades after her death, when her work had gone out of fashion, the accusation of unoriginality of her work started to surface. It’s impossible to pinpoint exactly what combination of factors led to the misunderstanding of her work in later years, but the heady cocktail surely included; the advent of photography, social changes, the popularity of Berlin wool work and pure misogyny about women’s textile practice and professionalism.

By the 1930s there was a persistent opinion in published sources that although she was an excellent needlewoman, she had no originality of design, therefore was not an artist. In reading articles about her work, I get the impression that someone published this opinion and it was repeated by lazy journalists and perpetuated by even lazier art historians. These opinion-formers did not bother to fully research the context in which she worked, or indeed compare her work to the countless other examples of pictorial embroideries which exhibit a wholly different skill level and artistry to that of Mary Linwood.

It has been a puzzle to me during this research to understand why her embroideries became associated with Berlin wool work, which is a vastly different style of stitching and with very different intent, although they both rely on paintings or pictorial imagery as their source. My theory is that as her work was dispersed after her death and the closure of her gallery, it has not been possible to properly study her surviving works in any great detail in museums. Leicester Museums & Galleries has by far the largest collection of her works, numbering around 15 (depending if you count some that are incorrectly attributed). The majority of these were acquired post-1945 when a centenary exhibition was mounted. Before this, there were a handful in this museum service and in one or two other collections, and the rest in private hands or lost.

Without seeing Mary Linwood’s work, it is hard to understand the originality of her stitching approach, the artistry of her translation of paintings to embroidery and the dynamism and personality in the way she handled thread. Black and white photos in magazines do no convey the skill or detail in her work, and it is perhaps understandable that her work was lumped in with other pictorial stitch work from both the Georgian period and later Victorian period which vary enormously in quality, design and technique. I have now seen all of her work in public collections in the UK, a couple of privately-owned pieces and of course all of the Leicester pieces and feel entirely qualified in saying that she was ground-breaking, original and innovative within the constraints and conventions of her time. My exhibition brings together the largest group of her work shown since 1845 and I hope will demonstrate just what an incredibly original artist she was and how unjust the criticism of her has been.

Mary Linwood: Art, Stitch and Life opens on 13th September and continues until 22nd February 2026 at Leicester Museum & Gallery. Entrance is free.

Events, talks and more can be found at marylinwood.co.uk

Let me know what you think